‘

By Amadi Chimaobi Kingsley

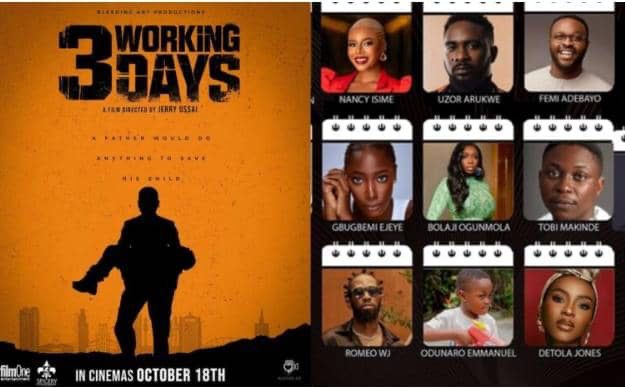

In reflecting on 3 Working Days, it’s important to note that while the film faced some controversy because of its marketing, which seemed to imply a character would wear a full hijab outfit, this doesn’t appear in the film. Instead, there’s only a brief scene with a character using a hijab mask, so the story doesn’t go as far as the promotional material suggested.

3 Working Days reminded me of the Naira scarcity era in 2023 during which Nigerians had to buy their money before having cash to spend.

This policy, intended to modernize banking, now proves perilous as digital payment failures leave Onari scrambling for solutions.

Onari’s life takes a brutal turn when he witnesses his wife, Valerie, fatally shot during an armed robbery that also injures their son, Jack. While we do not explicitly see Jack get shot, the film strongly implies his injury through its narrative context. With Valerie gone and Jack in critical condition, His desperation leads him to a chaotic bank scene, where he must contend with citizens also struggling against a failing system.

Directed by Jerry Ossai, 3 Working Days stars Emmanuel Odunayo, Detola Jones, Romeo Horsfall, Victor Osuagwu, Tobi Makinde, Gbubemi Ejeye, Linda_Osifo, Mike Afolarin, Deyemi Okanlawon and Nancy Isime, amongst others.

This narrative draws parallels to films like Saving Onome and Tokunbo, which similarly depict desperate parents struggling to save their sick children. However, while those narratives often focus on raising money, Onari’s unique situation revolves around his inability to access his funds, which adds a distinctive layer to his desperation. Imagine having the means, but you can’t access it.

This plot device amplifies the emotional stakes, underscoring the agony of helplessness that arises when love clashes with powerlessness. Although the film’s relatable angle is compelling, the lack of deeper psychological exploration leaves the viewer observing from afar rather than feeling Onari’s struggle viscerally.

I’ll admit it—our banking system can be a mess. Bankers can be rude, digital systems fail, and nonchalance can seem baked into the process. Nigerians know this firsthand. But the portrayal here borders on caricature. Onari’s plight is believable up to a point. He’s a man grieving his wife and desperate to save his son, but the version of banking incompetence served up in this movie feels more like a mockery than a reflection of reality. The script wants us to believe that this man—a supposedly well-off auto parts dealer who lives in the posh parts of Lagos and deals with luxury cars—has just one bank account. One.

Then comes the turning point we all saw coming from a mile away. The filmmakers couldn’t resist shoehorning in a subplot about Onari’s criminal past, clumsily introduced through a throwaway line from Bolaji Ogunmola’s character, Aunty Emma: “I thought you’d left that life behind.” That’s all it takes to set up the inevitable, Onari revisiting his old ways to secure the money his son needs. And, of course, this setup wouldn’t be complete without a clichéd dream sequence featuring Onari’s late wife on a beach, urging him to save their son at all costs. Subtlety? Nowhere in sight

The movie’s main conflict, the hostage situation, is a disappointment. Onari storms the bank, holding staff and customers at gunpoint to demand the processing of his delayed transaction. What should have been a moment of gripping tension becomes a dull, drawn-out ordeal. The pacing drags, the characters’ reactions feel unnatural, and the stakes never quite hit home. And Deyemi Okanlawon, while usually dependable in roles that are better tailored to his broody, sexy man aura, struggles to convey a believable measure of the desperation and anger that should define Onari’s character. His performance is energetic, sure, but it lacks the emotional depth that would make us feel his pain.

The supporting cast doesn’t fare much better. Nancy Isime, Mike Afolarin, Linda Osifo, and Mike Ezuruonye — all famous actors who are instantly recognizable faces and names deliver performances that feel phoned in. It’s a collective failure that leaves the audience disengaged and unimpressed.

And then there’s the writing. Oh, the writing. There’s a scene where a journalist covering the unfolding crisis dramatically asks: “Is this a bank robbery or a terrorist attack?” A terrorist attacks. In a local branch of a Nigerian bank? The sheer absurdity of that line encapsulates the film’s lack of self-awareness.

The story in 3 Working Days is the type that tries to work on viewers’ emotions but fails to captivate attention because of the directing. In real life, seeing a man struggling to care for his injured son after losing his wife is enough to evoke an emotional response. However, the movie couldn’t achieve that because there was no sense of something at stake. This doesn’t take away from the acting delivered by Deyemi Okanlawon, who starred as Onari. Emmanuel Odunayo, who starred as Onari’s son, also delivered good acting, especially the part where he was having something like a seizure at the hospital.

The essence of attending the cinema lies in the ability to feel immersed in the narrative, to escape reality, and to connect emotionally with the story only to be frustrated at the end of the day.

I couldn’t build any connection with the movie while at the cinema. It’s almost safe to say it provides a dull cinema experience, solid visuals that contribute to the film’s overall aesthetic. However, despite the competent technical execution, nothing particularly stands out to elevate the cinematic experience beyond the ordinary. It is just a low-budget film with no cinematic look, no color grading and nothing pleasing to the eyes. However, if the movie had just been left for YouTube, it would have been one of the best Nigerian movies on the streaming platform.

If Hollywood had handled the story idea that resulted in 3 Working Days, I would bet that I wouldn’t be able to raise criticism of the movie beyond a single point. I’ll advise the writer of the movie to focus on telling relatable stories about Nigeria, instead of stories of bank robbery, especially when there’s a lack of budget to make such a reality. Now I see why most producers prefer the romance comedy genre because it can be made interesting

Having noted the place of sound design in adding depth to action sequences, the film demonstrates a solid foundation in technical execution. A notable place of sound design in 3 Working Days is noticed in a scene which effectively creates unease with auditory cues, including simulated breathing that enhances the atmosphere, though it feels misplaced. However, the editing choices disrupt the film’s emotional resonance.

The movie also struggles to deliver action moments, especially the situation between Oani and Queen, portrayed by Nancy Isime. This shortcoming was, however, covered by the good soundtrack and the simulated sounds that added to the tension.

The rapid transitions between scenes undermine moments of emotional gravity that should linger with the audience, preventing them from fully absorbing the characters’ emotional journeys.

Additionally, noticeable costume continuity errors detract from the film’s credibility. For instance, Smart (Mike Afolarin) is seen wearing the same outfit on a different day, which raises questions about the narrative timeline. Similarly, an extra portraying a nurse appears in identical attire during two separate scenes, suggesting that these shots may have been filmed on the same day. While one might excuse the nurse’s uniform as standard attire, the framing of her appearances is strikingly similar, making the repetition more apparent.

These continuity errors disrupt immersion, as viewers may become distracted by inconsistencies that draw attention away from the story being told. Overall, the technical execution showcases a commendable effort, but the editing and continuity issues impact the film’s cohesiveness and emotional engagement.

3 Working Days is a 5/10 for me because it tries to be many things—a critique of government policies, a commentary on systemic corruption, an emotional family drama—but it succeeds at none. Its attempt to highlight the chaos of the cashless banking policy is half-hearted at best, and its portrayal of the Nigerian banking system as a bastion of villainy feels more like lazy storytelling than meaningful social commentary.

Leave a Reply