Valentine Obienyem

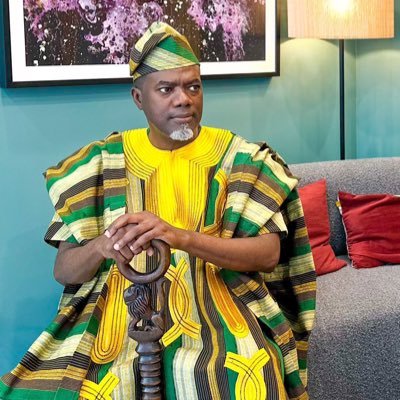

When Reno Omokri visited President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, he arrived not merely as a guest, but as a symbol – adorned in full Yoruba attire, wrapped in “adire” like a native son of the soil. But this was no celebration of national unity or cultural solidarity. It was a calculated performance, a sartorial soliloquy meant to signal allegiance: “I am with you. I belong. I am one of you.” He later justified his attire by claiming a general fondness for Nigerian fashion. Yet how many times since that carefully staged performance has he been seen in “isi agu” or any other symbol of his ancestral culture? Indeed, during the recent commissioning of part of the Lagos-Calabar Coastal Highway, did you notice how he was invisibly echoing to the Yoruba audience: “I hope you all see my attire? What else do you need me to do to demonstrate absolute loyalty?” In Omokri’s world, clothing is not worn to cover nakedness, it is wielded, as costume, as code, as currency in the court of power.

His writings have since followed suit. Where he once positioned himself as a noisy defender of Christianity under President Goodluck Jonathan, he now projects himself as a lover of Islam. The President is a Muslim. The Vice President is a Muslim. Reno’s pivot is not theological – it is strategic. He does not seek God; he seeks validation.

When Jonathan was in office, Reno painted his loyalty in the colours of Christian piety. Under Tinubu, he rewrites his devotion in the tones of Islamic admiration. What he loves is not faith or truth – it is relevance. His god is not the Creator, but the throne.

Yet let no one imagine this is a novel invention. He has not, in doing so, discovered a new demonstration in geometry. He joins a long tradition of men whose loyalty flows not from conscience, but from convenience.

Consider Alcibiades, the brilliant but unreliable Athenian who defected to Sparta, then to Persia, and finally back to Athens – each time shifting his allegiance to wherever power and protection lay. Alcibiades was a genius of adaptability, never a man of conviction. Reno, too, is not grounded in principles but in expediency. His ideological transformations are not Pauline conversions of the heart but calibrations of opportunity.

Even John Milton, the towering poet and early champion of liberty, was not immune to the seductions of power. In his youth, notably through his book, “ Areopagitica”, he rose in defence of freedom of speech, passionately opposing censorship and all forms of intellectual tyranny. Yet, after receiving office and favour under Oliver Cromwell, the Milton who once thundered against monarchy and authoritarianism softened his voice. The firebrand of liberty gave way to a more cautious defender of established power. It was not conviction that changed, but convenience – a familiar transformation in the corridors of influence. We see a modern echo of this in Reno Omokri, who once roared in righteous indignation against drug peddling, issuing grave warnings and condemnations. Today, that same man pours rhapsodies upon a figure widely suspected of such crimes, composing flattering tributes and justifying the unjustifiable. Like Milton in the shadow of Cromwell, Reno now moves in the glow of favour, abandoning principle for proximity to power.

Reno’s own pen would follow the same pattern if Nigeria descended into full-blown dictatorship. He would not resist it, he would rationalise it. He would call it “a necessary transitional mechanism,” or “a disciplined correction on the road to true democracy.” He would put gold leaf on a gulag and call it a necessary temple.

Men like Reno Omokri do not serve nations – they serve regimes. Their allegiance is not to enduring principles but to transient occupants of power. To reflect on such men is to confront the age-old chasm between statesmanship and politics. The statesman speaks for posterity; the politician performs for the moment. Reno and his ilk are not prophets – they are decorators of power. They do not call the palace to repentance; they rearrange its curtains to flatter the throne. Where truth demands confrontation, they offer choreography. Their loyalty is never to the soul of the nation, but to the shadow that sits on its highest seat. They speak not to awaken the conscience of the people, but to soothe the ego of the ruler. In every age, such men abound: ornamental, eloquent, and ultimately dispensable.

We have seen this theatre before. Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, the famously supple French diplomat, glided through the shifting sands of history with polished grace. He served the ancien régime, pledged fidelity to the Revolution, counselled Napoleon with cold efficiency, and bowed smoothly to the restored Bourbon monarchy – all without so much as a stumble. His brilliance lay not in statesmanship, but in the exquisite art of survival. He was loyal, yes—but only to the continuity of his own relevance. Like Reno Omokri, Talleyrand understood one unchanging principle: the regime may change, but the self must endure. For men of their mould, conviction is negotiable, allegiance is ornamental, and history is a stage upon which they endlessly reappear – ever present, ever adaptable, ever unburdened by the weight of moral consistency.

Then there is the immortal figure of the Vicar of Bray – a parable of pliability in ecclesiastical robes. With every turn of the crown, he turned his creed: Catholic under one monarch, Protestant under the next, then Catholic again, and once more Protestant – all to retain his parish and his pension. Doctrine shifted, altars changed, but the vicar remained immovably in place. His theology evolved not through revelation, but through calculation. In him, we see the sacred distorted into strategy – the pulpit converted into a platform for self-preservation. He did not preach truth; he practised tenure. Like Reno, his compass pointed not to conviction, but to convenience. The faith that mattered most was faith in remaining.

Or consider Petronius Arbiter, the languid yet lethal courtier of Emperor Nero – a man who perfected the art of surviving despotism through the velvet glove of charm. Known as the “arbiter elegantiarum”, he was not a man of truth but of tact, fluent in the language of flattery, and deft in the choreography of courtly submission. He mastered the subtle science of pleasing without conviction, of nodding without believing, of dressing servility in elegance. Under Nero’s erratic cruelty, Petronius thrived, not by resisting tyranny, but by styling it. In Reno Omokri, we see a modern incarnation: Petronius with a smartphone, draped not in togas but in trending hashtags, offering not counsel but curated praise, and navigating power not through ideas but through algorithms. Where Petronius wrote poetry for emperors, Reno composes tweets for regimes.

Need we search further? Reno’s tribe is vast, and his lineage long—stretching across centuries and continents, from palaces to parliaments, from cathedrals to cabinets. The names may change, the costumes may vary, but the performance remains hauntingly familiar. These are not the architects of nations; they are its decorators—men who gild the surface while rot festers beneath. They do not shape history; they flatter its tyrants. They are not prophets who trouble the throne, but courtiers who perfume it. In every age, they rise with the sun of power and vanish with its eclipse. Their loyalty is to relevance, their gospel is expediency, and their legacy is the silence they helped sustain. A nation may survive its enemies, but it rarely survives the embrace of such friends.

… Obienyem, a public affairs commentor wrote in from Lagos.

Leave a Reply