By Valentine Obienyem

Fr. Chigozie Jidere can always be trusted to draw life even from the driest readings. Today, he began with the conclusion: “You cannot serve two masters – God and Mammon.” From there, he drew four lessons from the readings, using the crafty steward in the Gospel as his central figure, and explained them with clarity.

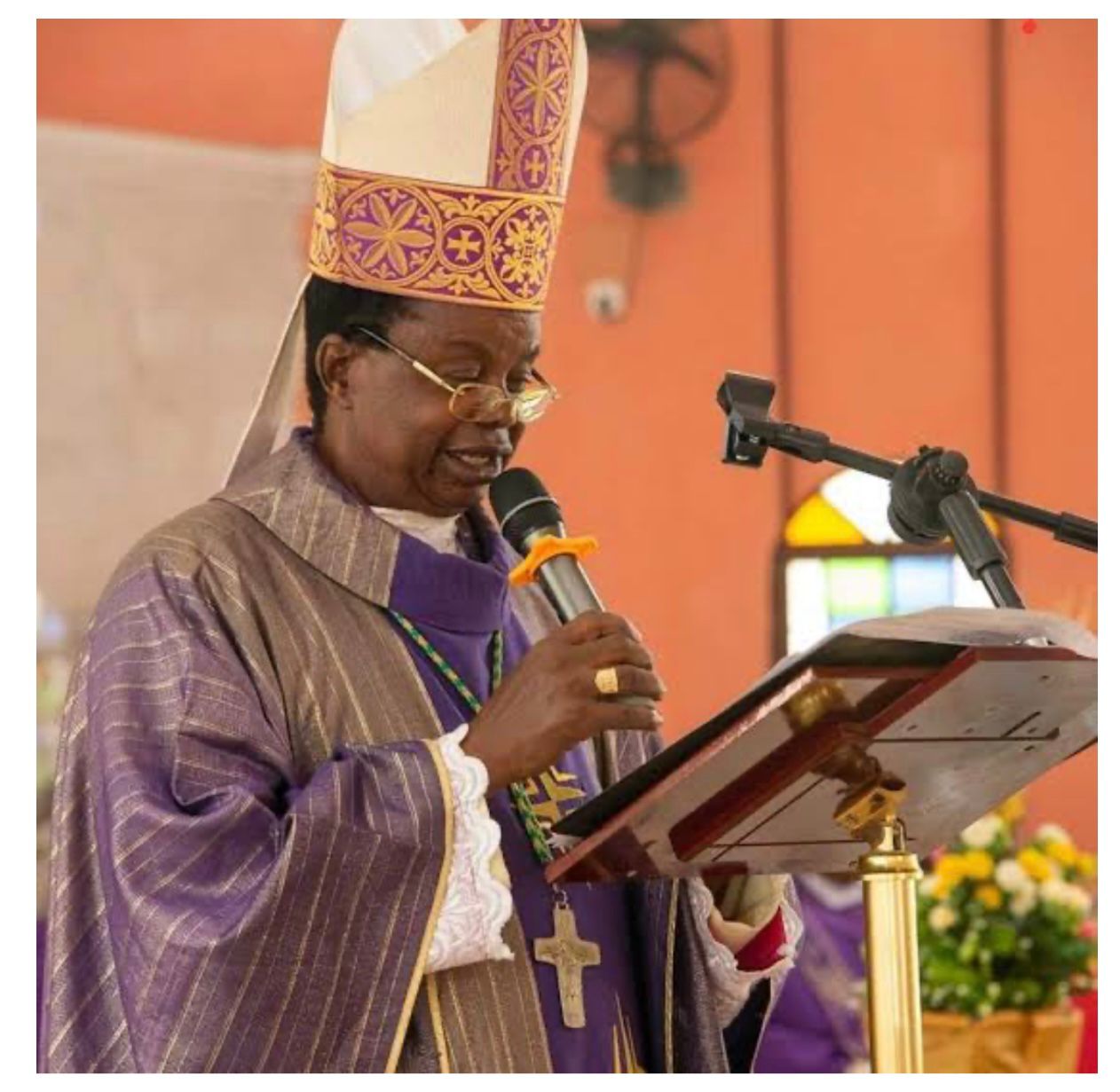

After Mass, Chris brought me my usual copy of “Fides.” As I turned its pages, a headline caught my eye: “Awka Diocese to Ban One-Session Textbooks and Graduation Ceremonies.” The story bore the picture of Bishop Paulinus Ezeokafor, whose calm dignity in carrying out his episcopal duties I have always admired. He is himself and nothing more, yet in that lies his strength. With less than two years to retirement, his legacy in Awka Diocese already speaks loudly. From Peter University to the re-naming of the retreat centre after Archbishop Obiefuna, even to diocesan structures I was reliably informed that he funded through personal goodwills, Bishop Ezeokafor has shown what it means to live for his people.

Bishop Ezeokafor lives in the poorest bishop’s house I have ever seen. While some other bishops are building palaces, he remains content there. When the old boys of Savio-Bosco visited him, we met him in his modest residence, whose parlour barely contained us, as he shared life with the seminarians in their spiritual year. Even the little things reflected his spirit: his simple, well-worn shoes bore the imprint of a shepherd unconcerned with vanities but intent on service. He does not set himself apart from his flock but quietly lives the humility he preaches.

Some years ago, I had the privilege of serving as Chairman at the feast of St. Dominic Savio Seminary. It was the first time Bishop Peter Okpaleke, then newly appointed Bishop of Ekwulobia and proprietor of the seminary, was attending the celebration. Seated with them on the high table, I watched with delight as Bishop Paulinus Ezeokafor, in his characteristic humility, quietly guided him: “Do this, bless the CMO members after they had presented their gift, do this, do that.” There was no trace of rivalry, only a fatherly joy in seeing his episcopal son take charge. Remember Okpaleke was his Chancellor for many years.

Years later, when Bishop Okpaleke was created Cardinal, I was present at his reception in the auditorium of the Urban University in Rome. Bishop Ezeokafor spoke not as one overshadowed, but as the happiest man, rejoicing in the elevation of one of his sons within the hierarchy of the Church. It was not just his words that mattered, but the genuine absence of envy – a quality rare even among the clergy, where subtle jealousies can sometimes be discerned despite attempts to conceal them.

As his retirement approaches, I hope he will leave us more than memories. An autobiography – or at least a biography – would preserve the story of his humble beginnings, his priestly journey, and his quiet but firm leadership as bishop.

Thinking of him drew my mind to bishops across history who defined the episcopal office. St. Ambrose of Milan embodied the bishop as a statesman of the Church – renouncing wealth, defending orthodoxy, composing hymns, and compelling emperors to repentance. St. Augustine of Hippo, once a restless seeker, became bishop at thirty-three, and through tireless preaching and writing, left theology of enduring value. St. Basil of Caesarea extended episcopal duty into social reform, establishing hospitals and orphanages, while St. Martin of Tours lived in poverty and won love through missionary work.

In modern times, the same spirit shone in St. Oscar Romero, martyred as the “voice of the voiceless,” and Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, who promoted a consistent ethic of life with pastoral gentleness. Bishop Fulton J. Sheen used radio and television to evangelise millions, while Cardinal Francis Arinze combined pastoral courage during the Biafran War with global interreligious dialogue and admirable orthodoxy. I love listening to his interviews, where his knowledge about the church is unrivalled. Cardinal Basil Hume, a Benedictine, showed that prayerful humility could harmonise with leadership. Together, they reveal that the bishop’s call – to teach, sanctify, and govern with courage and charity – transcends centuries.

Seen in this light, Bishop Ezeokafor rightly stands in the noble company of the great bishops before him. He has not only defended and protected the Church but also expanded its mission through concrete works of mercy: founding hospitals, orphanages, homes for the elderly, schools, and a university. His pastoral letters speak with clarity and conviction, addressing both the needs of the Church and wider society.

In every decision, he weighs the impact on the faithful, ensuring that the Church remains both a moral guide and a source of practical support. Critics often accuse Catholic schools of charging high fees, yet compared to many others they remain relatively affordable. I once discussed this with the Diocesan Education Secretary, Fr. Maximus Okonkwo, who explained that despite rising costs, the bishop resists arbitrary increases, mindful of the struggles of families. That same spirit reveals itself in the hospitals he oversees. At Regina Caeli, I once witnessed an accident victim rushed into emergency care without registration or payment demanded for life to be saved first – an eloquent testimony to Bishop Ezeokafor’s conviction, along the mind of the Church, that humanity must always come before bureaucracy.

The Fides story that prompted these reflections is another good example. Bishop Ezeokafor endorsed Imo State’s ban on one-session textbooks and indiscriminate graduation ceremonies, promising to enforce the same in Awka diocesan schools if the Anambra State government failed to act. I recall that Anambra had already moved in that direction, which is commendable. I also heard how the State Commissioner for Education, Prof. Ngozi Chuma-Udeh intervened when a certain primary school imposed “nomination fees” on pupils aspiring to be prefects, with some paying as much as ₦5,000 depending on the post sought. If unchecked, such practices would only invite corruption, with some useless parents of today giving children money to their children to buy votes – a tragic distortion of formative education.

I recently had a personal experience that highlighted the same problem. After paying the approved school fees for my daughter, I was unexpectedly asked for an additional cash of ₦5,000 as “maintenance fees.” Such piecemeal levies create unnecessary burdens for parents. Why can’t schools consolidate all charges into a transparent fee structure, breaking down tuition, electricity, maintenance, and other costs clearly, rather than introducing arbitrary demands? When schools operate in these shadowy ways, they risk corrupting the very students they should be forming – offering them scorpions when their parents brought them for bread.

Bishop Ezeokafor’s episcopacy reminds us that true leadership is measured by fidelity, service, and courage. He has shown that the bishop’s staff is a shepherd’s rod, guiding, protecting, and correcting with love. The work of bishops is never easy. Imagine the headaches of running a company with fewer than twenty employees, and then consider the challenge of guiding a diocese of millions, with hundreds of priests – some older, some more educated, all with different temperaments and expectations. To hold such a body together requires not only learning and prudence but also deep faith, patience, and humility.

As he approaches retirement, Bishop Ezeokafor’s legacy stands as a challenge to all – clergy and laity alike – to place humanity before bureaucracy, truth before convenience, and service before self. In him, Awka Diocese has had not just a leader but a father, and his life’s witness will continue to teach long after his fast approaching retirement.

Leave a Reply